Role Of International Institutions Descriptive Question And Answers

Question 1. State the relationship between the TRIPS agreement and the ‘pre-existing international conventions’ covered under it.

Answer:

The relationship between the TRIPS agreement and the ‘pre-existing international conventions’ covered under it

- The TRIPS Agreement says WTO member countries must comply with the substantive obligations of the main conventions of WIPO the Paris Convention on industrial property, and the Berne Convention on copyright (in their most recent versions).

- Except for the provisions of the Berne Convention on moral rights, all the substantive provisions of these conventions are incorporated by reference. They therefore become obligations for WTO member countries under the TRIPS Agreement – they have to apply these main provisions and apply them to the individuals and companies of all other WTO members.

- The TRIPS Agreement also introduces additional obligations in areas that were not addressed in these conventions or were thought not to be sufficiently addressed in them.

- The TRIPS Agreement is therefore sometimes described as a “Berne and Paris- plus” Agreement.

- The text of the TRIPS Agreement also makes use of the provisions of some other international agreements on intellectual property rights:

- WTO members are required to protect integrated circuit layout designs under the provisions of the Treaty on Intellectual Property in Respect of Integrated Circuits (IPIC Treaty) together with certain additional obligations.

- The TRIPS Agreement refers to several provisions of the International Convention for the Protection of Performers, Producers of Phonograms, and Broadcast in Organizations (Rome Convention), without entailing a general requirement to comply with the substantive provisions of that Convention.

Question 2. What is the relationship between the TRIPS Agreement and the Pre-existing International Conventions covered under it?

Answer:

The relationship between the TRIPS Agreement and the Pre-existing International Conventions covered under it

The TRIPS Agreement says WTO member countries must comply with the substantive obligations of the main conventions of WIPO, the Paris Conventions on Industrial Property, and the Berne Convention on Copyright (in their most recent versions).

Except for the provisions of the Berne Convention on moral rights, all the substantive provisions of these conventions are incorporated by reference.

They, therefore, become obligations for WTO member countries under the TRIPS Agreement – they have to apply these main provisions and apply them to the individuals and companies of all other WTO members.

The TRIPS Agreement also introduces additional obligations in areas that were not addressed in these conventions or were thought not to be sufficiently addressed in them. The TRIPS Agreement is therefore sometimes described as a Berne and ‘Paris-Plus’ Agreement.

The TRIPS Agreement contains references to the provisions of certain pre-existing intellectual property conventions.

According to Article 2.1 of the Agreement, the WTO Members shall, in respect of Parts 2, 3, and IV of the Agreement, comply with Articles 1 through 12, and Article 19, of the Paris Convention (1967) (the Stockholm Act of 14 July 1967 of the Paris Convention for the Protection of Industrial Property).

Article 9.1 of the Agreement requires Members to comply with Articles 1 through 21 Berne Convention (1 971) and the Appendix thereto (the Paris Act of 24 July,

1971 of the Berne Convention for the Protection of Literary and Artistic Works). However, Members do not have rights or obligations under the TRIPS Agreement in respect of the rights conferred under Article 6b of that Convention, i.e. the moral rights, or of the rights derived therefrom.

As regards the protection of the layout designs of integrated circuits, Article 35 of the Agreement requires Members to comply with Articles 2 through 7 of the Treaty on Intellectual Property in respect of Integrated Circuits, adopted at Washington on 26 May 1989.

The Agreement contains some references to certain provisions of the Rome Convention (the International Convention for the Protection of Performers, Producers of Phonograms and Broadcasting Organizations, adopted at Rome on 26 October 1961).

However, there is no general obligation to comply with the substantive provisions of that Convention.

The TRIPS Agreement provisions on copyright and related rights clarify or add obligations on several points:

The TRIPS Agreement ensures that computer programs will be protected as literary works under the Berne Convention and outlines how databases must be protected under copyright; It also expands international copyright rules to cover rental rights.

Authors of computer programs and producers of sound recordings must have the right to prohibit the commercial rental of their works to the public.

A similar exclusive right applies to films where commercial rental has led to widespread copying, affecting copyright owners’ potential earnings from their films; It says performers must also have the right to prevent unauthorized recording, reproduction, and broadcast of live performances (bootlegging) for no less than 50 years.

Producers of sound recordings must have the right to prevent the unauthorized reproduction of recordings for 50 years.

The test of the TRIPs agreement also makes use of the provisions of some other international agreements on intellectual property rights:

WTO members are required to protect “Integrated Circuit Layout Designs” under the provisions of the Treaty on Intellectual Property In Respect of Integrated Circuits (IPIC Treaty) together with certain additional obligations.

The TRIPS Agreement refers to several provisions of the International Convention for the Protection of Performers, Producers of Phonograms, and Broadcasting Organizations (Rome Convention) without entailing a general requirement to comply with the substantive provisions of that Convention.

Article 2 of the TRIPS Agreement specifies that nothing in Paris 1 to 4 of the agreement shall derogate from existing obligations that members may have to comply with each other under the Paris Convention, the Berne Convention, the Rome Convention, and the Treaty on Intellectual Property in respect of Integrated circuits

Question 3. The Universal Copyright Convention (UCC) was developed by the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) as an alternative to the Berne Convention for those states that disagreed with aspects of the Berne Convention, but still wished to participate in some form of multilateral copyright protection. Identify the limitation of the Berne Convention and why the Berne Convention states also became a party to the UCC.

Answer:

The first multilateral agreement on copyright was the Berne Convention which was concluded in 1886 and was meant to protect literary and artistic works.

A country joining the Convention has to provide copyright protection to literary and artistic works of member countries in its territory and is also entitled to enjoy reciprocal protection from others. Ninety countries are at present members of the Berne Convention.

The post-Second World War era saw the emergence of the need for protecting copyright on a universal basis. Till then countries in North America were not a party to the Berne Convention and copyright protection in these countries was governed by various national and regional agreements.

The Universal Copyright Convention (UCC), adopted in Geneva, Switzerland, in 1952, is one of the two principal international conventions protecting copyright; the other is the Berne Convention.

The UCC was developed by the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) as an alternative to the Berne Convention for those states that disagreed with aspects of the Berne Convention but still wished to participate in some form of multilateral copyright protection.

These states included developing countries as well as the United States and most of Latin America.

The former thought that the strong copyright protections granted by the Berne Convention overly benefited Western, developed, copyright-exporting nations, whereas the latter two were already members of the Buenos Aires Convention, a Pan-American copyright convention that was weaker than the Berne Convention.

The Berne Convention states also became a party to the UCC, so that their copyrights would exist in non-Berne convention states.

In 1973, the Soviet Union joined the UCC. The United States only provided copyright protection for a fixed, renewable term, and required that for a work to be copyrighted it must contain a copyright notice and be registered at the Copyright Office.

The Berne Convention, on the other hand, provided for copyright protection for a single term based on the life of the author and did not require registration or the inclusion of a copyright notice for copyright to exist.

Thus the United States would have to make several major modifications to its copyright law to become a party to it.

At the time the United States was unwilling to do so. The UCC thus permits those states which had a system of protection similar to the United States for fixed terms at the time of signature to retain them.

Eventually the United States became willing to participate in the Berne convention, and change its national copyright law as required. In 1989 it became a party to the Berne Convention as a result of the Berne Convention Implementation Act of 1988.

Read the following case on patent law and answer the questions that follow:

Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights (TRIPS) defines geographical indication as “goods originating in the territory of a member, or a region or locality in that territory, where a given quality, reputation, or another characteristic of the goods is essentially attributable to its geographical origin”.

In the Indian legal system, Geographical Indication (Gl) is governed by the Geographical Indications of Goods (Registration and Protection) Act, of 1999. A case relating to GI is that of ‘Basmati rice’ being patented in the United States of America (USA).

Basmati rice is regarded as the ‘queen of fragrance or the perfumed one’ and is also acclaimed as the ‘crown jewel’ of South Asian rice.

It is treasured for its intense fragrance and taste, famous in national as well as international markets. This kind of rice has been grown in the Himalayan hills, Punjab, Haryana, and Uttar Pradesh since times immemorial.

Basmati is the finest quality of rice, long-grained, and the costliest in the world. Agricultural and Processed Food Products Export Development Authority (APEDA) states India to be the second largest exporter of rice after China.

The USA is a major importer of Basmati rice totalling 45,000 tonnes. An important case in the history of Gl and bio-piracy arose in 1997. Royal Rice Tec Inc.

(RRT), a tiny American rice company with an annual income of around US $10 million and working staff totaling 120, produces a small fraction of the world’s (Basmati-like) rice with names ‘Kasmati’ and Texmati’.

RRT had been trying to enter the world rice market for a long but in vain.

On 2nd September 1997, RRT was issued a patent for its Basmati rice lines and grains by the United States Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO) bearing patent number 5663484, which gave it the ultimate rights to call the odoriferous rice ‘Basmati’ within the US and label it the same for export internationally.

According to RRT, its invention of Basmati rice relates to novel rice lines, which affords novel means for determining cooking and which has unique starch properties, etc.

Since times immemorial, the majority of farmers from India have been sustaining the cultivation of Basmati rice and have been among the leading rice producers of the world. The cultivation of rice is not merely a life sustainer but also a part of socio-culture in India. Basmati rice produced in India has been exported to countries like Saudi Arabia and the UK. Basmati is a ‘brand name’ of the rice grown in India.

Two Indian NGOs, namely, the Centre for Food Safety, an international NGO that campaigns against bio-piracy, and the Research Foundation for Science, Technology, and Ecology, an Indian environmental NGO, objected to the patent granted by USPTO and filed petitions in the USA. Council for Scientific and Industrial Research (CSIR), a Government of India organization also objected to the patent granted to RRT.

They demanded an amendment to US Rice Standards because the term ‘Basmati’ can be used only for the rice produced/grown in the territories of India.

According to RRT, the invention relates to novel rice lines and to plants and grains of these lines. The invention also relates to a novel means for determining the cooking and starch properties of rice grains and identifying desirable rice lines.

Specifically, one aspect of the invention relates to novel rice lines whose plants are semi-dwarf in stature and give high-yielding rice grains having characteristics similar or superior to those of good quality Basmati rice. Another aspect of the invention relates to novel rice lines produced from novel rice lines.

The invention provides a method for breeding these novel lines. A third aspect relates to the starch index (SI) of the rice grain, which can predict the grain’s cooking and starch properties and select desirable segregates in rice breeding programs.

The Government of India reacted immediately after learning of the Basmati patent issued to RRT, stating that it would approach the USPTO and urge them to re-examine the patent to a US firm to grow and sell rice under the Basmati brand name, to protect India’s interests, particularly those of growers and exporters.

Furthermore, a high-level Inter-Ministerial Group comprising representatives of the Ministries and Departments of Commerce, Industry, External Affairs, Agriculture and Bio-Technology, CSIR, All India Rice Exporters Association (AIREA), APEDA and Indian Council of Agricultural Research (ICAR) was mobilized to begin an in-depth examination of the case.

In the presence of widespread uprising among farmers and exporters, India as a whole feels confident of being able to successfully challenge the Basmati patent by RRT, which got a patent for three things: Growing rice plants with certain characteristics identical to Basmati, the grain produced by such plants and the method of selecting the rice plant based on a starch index (SI) test devised by RRT.

The lawyers plan to challenge this patent on the basis that the abovementioned plant varieties and grains already exist and thus cannot be patented.

In addition, they accessed some information from the US National Agricultural Statistics Service in its Rice Yearbook 1997, released in January 1998 to the effect that almost 75 percent of US rice imports are Jasmine rice from Thailand and most of the remainder are from India, Varieties that cannot be grown in the US.

This piece of information is sought to be used as a weapon against RRT’s Basmati patent. Indians feel that the USPTO’s decision to grant a patent for the prized Basmati rice violates the International Treaty on TRIPS.

The President of the Associated Chambers of Commerce (ASSOCHAM) said that Basmati rice is traditionally grown in India and granting a patent to it violates the Geographical Indications Act under the TRIPS.

The TRIPS clause defines Geographical indication as “a good originating in the territory of a member, or a region or locality in that territory, where a given quality, reputation, or other characteristic of the goods is essentially attributable to its geographical origin.”

As a result, it is safe to say that Basmati rice is as exclusively associated with India as Champagne is with France and Scotch Whiskey with Scotland.

Indians argue that just as the USA cannot label their wine as Champagne, they should not be able to label their rice as Basmati.

If the patent is not revoked in the USA, because, unlike the Turmeric case, rice growers lack documentation of their traditional skills and knowledge, India may be forced to take the case to the WTO for an authoritative ruling based on violation of the TRIPS.

In the wake of the problems with patents that India has experienced in recent years, it has realized the importance of enacting laws for conserving biodiversity and controlling piracy as well as intellectual property protection legislation that conforms to international laws.

There is a widespread belief that RRT took out a patent on Basmati only because of weak, non-existent Indian laws and the Government’s philosophical attitude that natural products should not be patented.

According to some Indian experts in the field of genetic wealth, India needs to formulate a long-term strategy to protect its bio-resources from future bio-piracy and/or theft.

British traders are also supporting India. According to Howard Jones, marketing controller of the UK’s privately owned distributor Tilda Ltd., “true Basmati can only be grown in India.

We will support them in any way if it’s necessary”. The Middle East is also supported by labeling only Indian rice as Basmati.

Government and government agencies have gathered the necessary data and information to support their case and to prevent their cultural heritage from being taken away from them.

Whether Royal Rice Tec Inc. is guilty of bio-piracy? Explain

Question 1. Discuss whether the decision of the USPTO to grant a patent for the valued Basmati rice violates TRIPS.

Answer:

The decision of the USPTO to grant a patent for the valued Basmati rice violates TRIPS

Bio-piracy in general can be defined as the practice of commercially exploiting naturally occurring biochemical or generic material, especially by obtaining patents that restrict its future use, while failing to pay reasonable compensation to the community from which it originates.

It is a manipulation of the Intellectual Property Rights by corporations, entities, and persons to gain exclusive control over the national genetic resources, without giving adequate recognition and remuneration to the original possessors of those resources.

Indigenous people possess significant old knowledge that allowed them to sustainably live and make use of biological arid gone within their natural environment for generations.

Traditional knowledge naturally includes a deep understanding of ecological processes or d e c ability to sustainably extract useful products from the local habitat.

Examples of bio-piracy include the recent patents granted by the Patent and Trademark Office to different American companies or Turmeric’, ‘Neem’ and most notably, ‘Basmati Rice.

All three products have been indigenous to the Indian subcontinent since time immemorial.

RRT’s actions constitute bio-piracy because it infringe the provisions of the Convention on Biological Diversity (‘CBD; in short), which provides for the State’s sovereignty over its genetic resources.

The CBD aims to bring about a system for the conservation and sustainable use of biological diversity and the fair and equitable sharing of benefits arising from the use of their genetic resources.

How RRT established its patent demonstrates that it has ignored the contributions of the local communities in the production of Basrnati and that it does not intend to share the benefits accruing from the use of genetic resources.

This includes both the informal contributions of the farmers who have been growing Basrnati for hundreds of years in India and the neighboring sub-continents, as well as the more formal, scientific breeding work that has been done by rich research institutes to evolve better varieties of Basrnati.

RRT has capitalized on this work of the indigenous community by taking out a Patent on Basrnati and intends to monopolize the commercial use of past research, without giving any recognition or remuneration to those who played a key role in the evolution and breeding of Basrnati rice in its natural habitat.

The involved in the Basrnati patent is therefore classified threefold namely a theft of the collective intellectual and biodiversity heritage of Indian farmers, a theft from Indian traders and exporters whose markets are being stolen by RRT, and finally, a deception of consumers because RRT is using a stolen name Basmati for rice which are derived from Indian rice but not grown in India, and therefore are not the same quality.

RRT has unfairly appropriated and exploited the genetic resources in this case by attempting to gain exclusive control of its development and propagation through a legal process that threatens the traditional rights of the original possessors of the resource.

The key concern relates to RRT’s use of the term ‘Basmati’ to describe its rice lines and grains.

‘Basmati’ is associated with the specific aromatic rice variety grown in India and taking out a Patent on the use of the term to describe its invention.

RRT has potentially reversed the culpability and made India the violator of RRT’s legally protected rights although the latter are the original possessors and breeders of the ‘Basmati’ rice. RRT is guilty of bio-piracy.

Question 2. How does the patent granted to RRT by the USPTO impact the farmers in India?

Answer:

The grant of a Patent to RRT on Basmati does violate certain provisions of TRIPS.

The TRIPS Agreement provides for certain standards to be fulfilled before granting of protection in the form of Intellectual Property Rights which are particularly relevant for determining whether there was any act of bio-piracy involved in the above case.

RRT’s patent on Basmati violates Article 22 of the TRIPS, which deals with Geographical Indications.

As defined under Article 22(1) of TRIPS, Geographical Indications are indications that identify a good as originating in the territory of a member, or a region or locality in that territory, where a given quality, reputation, or other features of the goods is essentially attributable to its geographical origin.

For example, wines and liquors are most commonly associated with Geographical Indications of their place of origin.

The term “Champagne” can only be used to describe a wine that has been produced in the Champagne region of France, the area from which the wine derives its name.

Wine with similar features but produced in another part of the world, cannot be described as “Champagne”.

“Champagne” remains an exclusive product and the name is the exclusive property of the French company producers. A similar case of Geographical Indication is that of “Scotch”, a whisky, which is produced in the Scottish highlands.

This protection for Geographical Indications for wines and liquors is outlined in Article 23 of the TRIPS.

Basmati falls in this category because it enjoys the same closely linked and exclusive relationship with its place of origin in India.

In India, Basmati is grown mainly in some scattered districts of Punjab, Haryana, and Uttar Pradesh. India grows tons of rice annually.

Hence, it is clear that Basmati rice, as it is traditionally recognized, is geographically unique in its origin.

The Basmati Patent resulted in a brief diplomatic crisis between India and the United States with India threatening to take the matter to WTO as an infringement of TRIPs since a Gl product cannot be patented under the provision of TRIPs.

However, ultimately, due to review decisions by the United States Patent Office, RRT has lost most of its claims of the patent, including, most significantly, the right to call their rice “basmati.”

There is a precedent also for the recognition of Basmati as a Geographical Indication by the International Buyers.

The European Commission recognizes India’s and other neighboring sub-continents’ rights to products bearing their distinctive geographical indications, allowing only Basmati rice that has been grown in India and the neighboring sub-continent to be labeled as such.

Similarly, the code of practice for rice in the UK, the largest market for Basmati rice in Europe, describes long grain, aromatic rice grown only in India and neighboring sub-continent as Basmati.

Question 3. Whether adequate legislation exists in India concerning geographical indications? Discuss the salient features.

Answer:

RRT’s patent could impact Indian farmers in the following two possible ways:

- By displacement of Basmati exports from India; and

- By monopolizing the Basmati seed supplies.

Regarding the first possible inroads that may be made by the USA into the South Asian export markets, it is a matter of concern to the Indian farmers.

In 1995, the USA produced 7.89 million metric tons of rice and in the same year, India produced 122.37 million metric tons of rice.

American rice exports are significantly greater than India’s, implying that the USA has a greater production surplus. In 1994 itself, the USA exported more volumes of rice as compared to India and its neighboring sub-continent.

Hence, owing to the RRT’s patent, it seems that potential exists for the USA to displace Indian Basmati exports.

Criticism from Indian rice farmers logically ensued, as many were forced to pay royalties to the conglomerate.

The production and cultivation of Basmati has with it a history dating back to centuries ago.

For farmers, the grain is an entity that is constantly evolving.

In the context of India, Basmati rice has always been considered a common resource dependent upon word-of-mouth knowledge and transfer.

Using this logic, Rice Tec alleged that the ‘Basmati name was in the public domain and that by patenting it; they were in actuality protecting its name and origins.

RRT soon came out with hybrid versions of Kasmati, Texmati, and Jasmati, which for rural farmers clearly illustrated the profit-based interest of the conglomerate.

Through its acquisition, RRT patented some 22 varieties of rice.

One of which was Basmati 867, a rice grain that was very similar to the original Basmati but was advertised to have a less chalky more refined taste.

The severity of RRT’s biopiracy cannot be underestimated, as the conglomerate was claiming to have invented the physical characteristics of Basmati such as the plant height and grain length.

By claiming ownership of the rice plant itself, RRT was directly threatening rural farming communities.

A second and more serious threat is that, through its patent, RRT could acquire a monopoly over Basmati seed supply to the sub-continent.

It is a premier developer of commercial hybrid rice varieties in the USA.

A precedent exists that foreign agri-business companies have bought hybrid seeds from Third World Countries.

For instance, Monsanto has recently undertaken a joint venture with Grameen Bank in Bangladesh to distribute its hybrid seeds through loan packages to small farmers.

Hybridization is likely to harm small farmers more as they are less able to absorb the higher seed costs. In its extreme form, such hybridization could harm genetic diversity and deplete farmlands of their intrinsic resources.

Question 5. Explain the provisions for registration of geographical indications in India.

Answer:

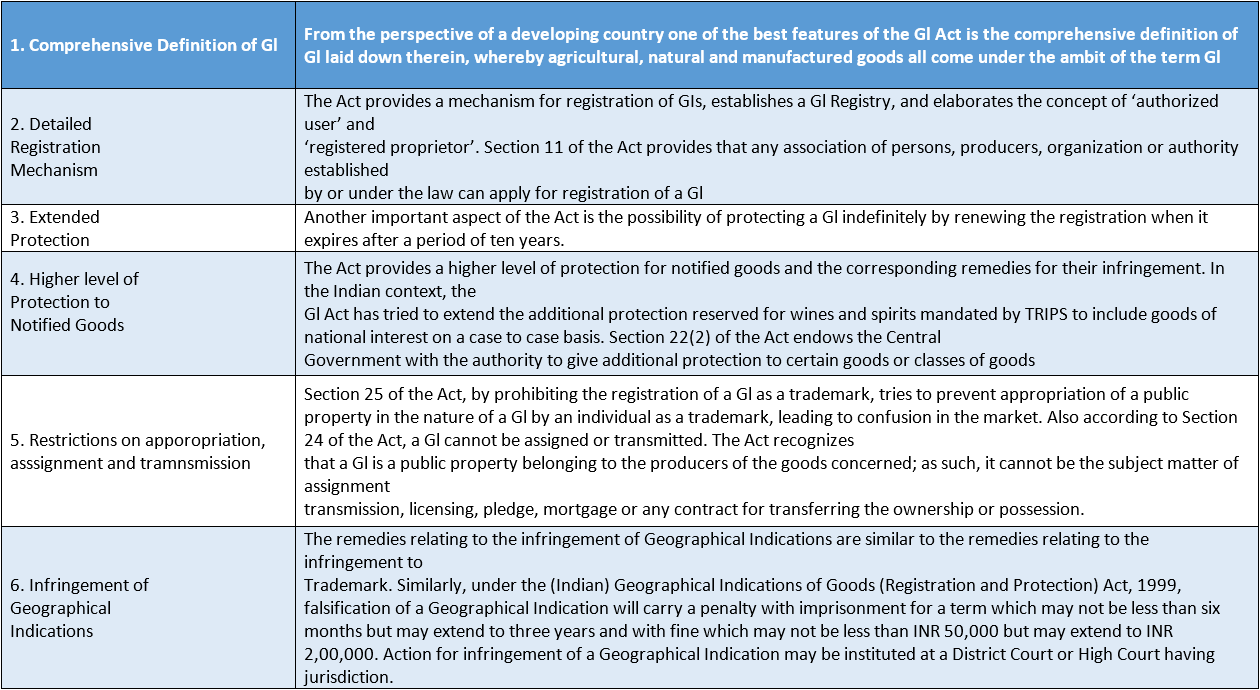

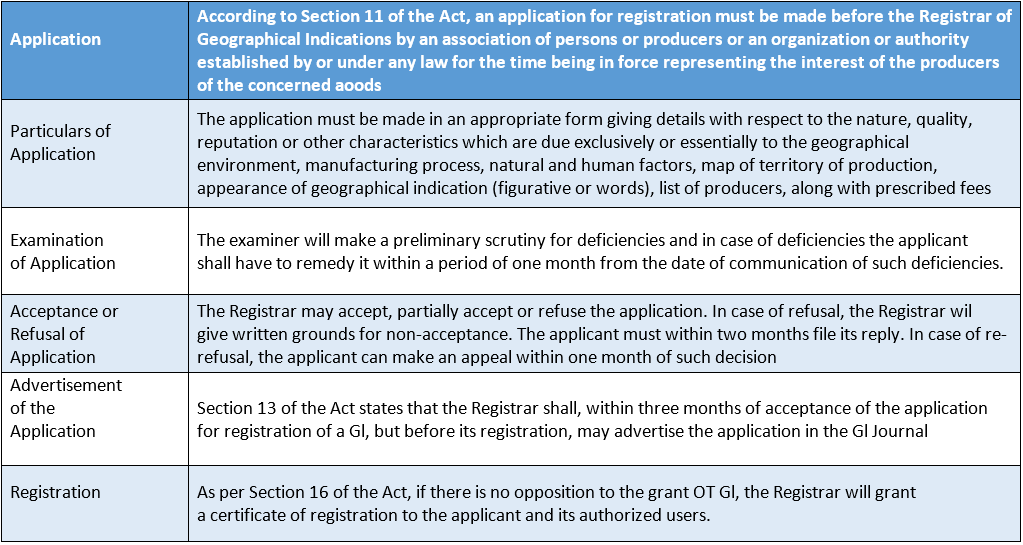

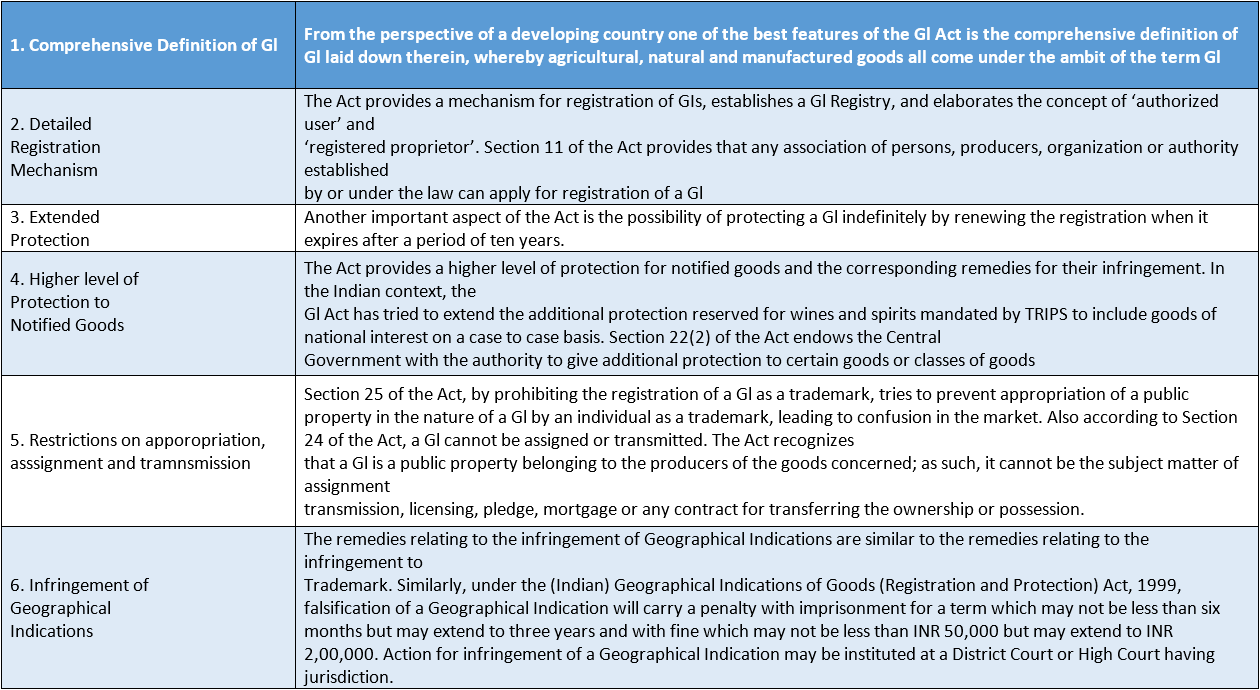

In India, the legal system for Geographical Indication (‘Gl’ in short) protection has been developed very recently.

The provisions in that regard are contained in the Geographical Indications of Goods (Registration and Protection) Act (‘Gl Act’ in short) which was enacted in the year 1999 and came into force only in September 2003.

Available relief include:

- Injunction,

- Discovery of documents.

- Damages or accounts of profits

- Delivery of the infringing labels and indications for destruction or erasure.

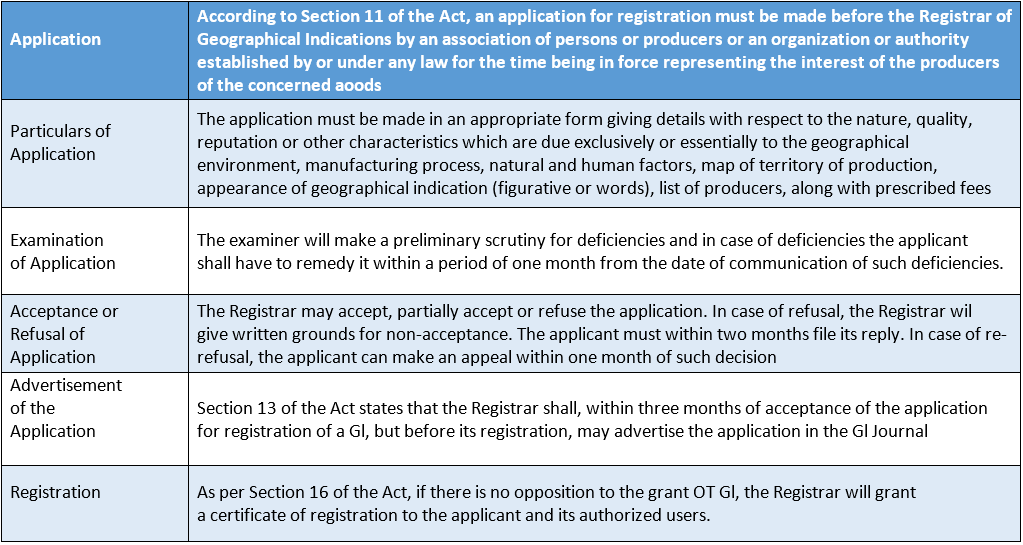

Provisions for the registration on Geographical Indication are as follows:

Section 8 of the Geographical Indications of Goods (Registration & Protection) Act, 1999 provides that a geographical indication may be registered in respect of any or all of the goods, comprised in such class of goods as may be classified by the Registrar and in respect of a definite territory of a country, or a region or locality in that territory, as the case may be.

The Registrar may also classify the goods by the International classification of goods for registration of geographical indications and publish in the prescribed manner in an alphabetical index of classification of goods.

Any question arising as to the class within which any goods fall or the definite area in respect of which the geographical indication is to be registered or where any goods are not specified in the alphabetical index of goods published shall be determined by the Registrar whose decision in the matter shall be final.

Topic Not Yet Asked But Equally Important For Examinations Descriptive Questions

Question 1. Discuss in brief at least five leading International Instruments concerning Intellectual Property Rights.

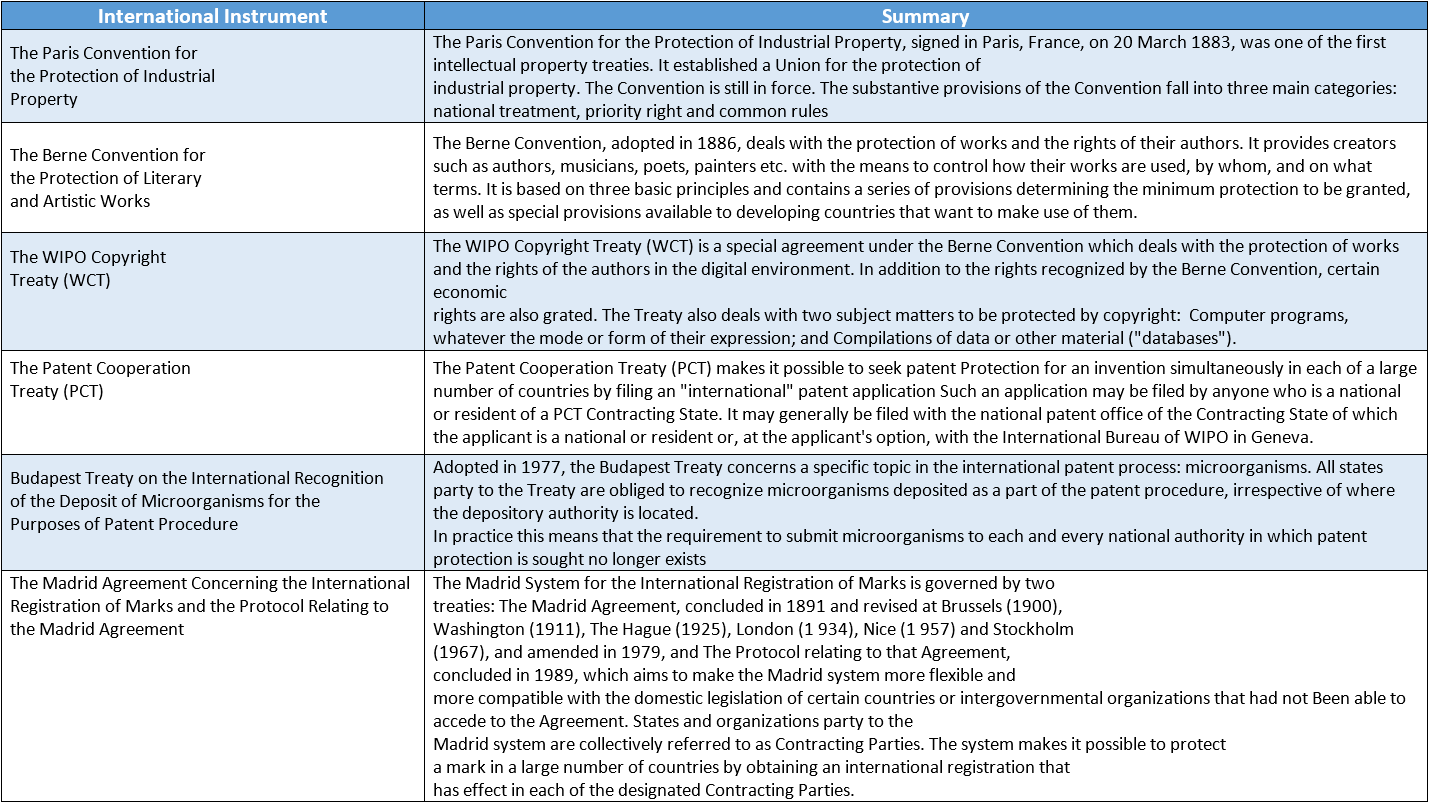

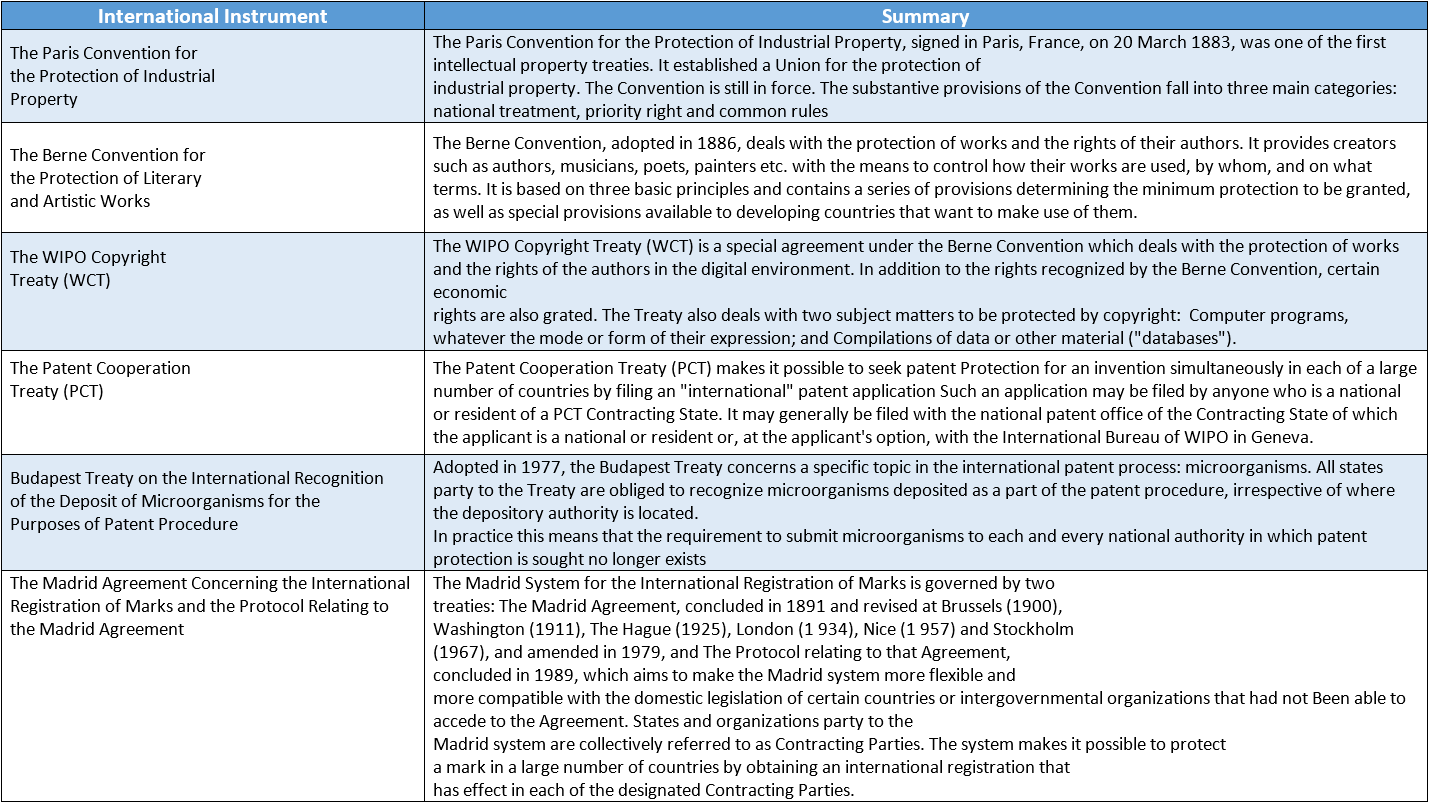

Answer:

Introduction to the leading International Instruments concerning Intellectual Property Rights: Intellectual property has a dual nature, i.e. it has both a national and international dimension.

For instance, patents are governed by national laws and rules of a given country, while international conventions on patents ensure minimum rights and provide certain measures for enforcement of rights by the contracting states.

Strong protection for intellectual property rights (IPR) worldwide is vital to the future economic growth and development of all countries.

Because they create common rules and regulations, international IPR treaties, in turn, are essential to achieving the robust intellectual property protection that spurs global economic expansion and the growth of new technologies.

A list of some leading Instruments concerning Intellectual Property Rights is as below:

- The Paris Convention for the Protection of Industrial Property

- The Berne Convention for the Protection of Literary and Artistic Works

- The WIPO Copyright Treaty (WCT)

- The Patent Cooperation Treaty (PCT)

- Budapest Treaty on the International Recognition of the Deposit of Microorganisms for Patent Procedure

- The Madrid Agreement Concerning the International Registration of Marks and the Protocol Relating to the Madrid Agreement

- The Hague Agreement Concerning the International Deposit of Industrial Designs

- The Trademark Law Treaty (TLT)

- The Patent Law Treaty (PLT)

- Treaties on Classification

- Special Conventions in the Field of Related Rights: The International Convention for the Protection of Performers, Producers of Phonograms and Broadcasting Organizations (“the Rome Convention”)

- Other Special Conventions in the Field of Related Rights

- The WIPO Performances and Phonograms Treaty (WPPT)

- The International Convention for the Protection of New Varieties of Plants

- The Agreement on Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights

Question 2. Write a brief note on the Berne Convention.

Answer:

Berne Convention

The Berne Convention deals with the protection of works and the rights of their authors.

It is based on three basic principles and contains a series of provisions determining the minimum protection to be granted, as well as special provisions available to developing countries that want to make use of them.

1. The three basic principles are the following:

- Works originating in one of the Contracting States (that is, works the author of which is a national of such a State or works first published in such a State) must be given the same protection in each of the other Contracting States as the latter grants to the works of its nationals (principle of “national treatment”).

- Protection must not be conditional upon compliance with any formality (principle of “automatic” protection).

- Protection is independent of the existence of protection in the country of origin of the work (principle of “independence” of protection).

- If, however, a Contracting State provides for a longer term of protection than the minimum prescribed by the Convention and the work ceases to be protected in the country of origin, protection may be denied once protection in the country of origin ceases.

2. The minimum standards of protection relate to the works and rights to be protected, and to the duration of protection:

- As to works, protection must include “every production in the literary, scientific and artistic domain, whatever the mode or form of its expression” (Article 2(1) of the Convention).

- Subject to certain allowed reservations, limitations, or exceptions, the following are among the rights that must be recognized as exclusive rights of authorization:

- The right to translate

- The right to make adaptations and arrangements for the work

- The right to perform in public dramatic, dramatico-musical and

musical works - The right to recite literary works in public

- The right to communicate to the public the performance of such works

- The right to broadcast (with the possibility that a contracting

- The state may provide for a mere right to equitable remuneration instead of a right of authorization)

- The right to make reproductions in any manner or form (with the possibility that a Contracting State may permit, in certain special cases, reproduction without authorization, provided that the reproduction does not conflict with the normal exploitation of the work and does not unreasonably prejudice the legitimate interests of the author; and the possibility that a Contracting State may provide, in the case of sound recordings of musical works, for a right to equitable remuneration)

- The right to use the work as a basis for an audiovisual work, and the right to reproduce, distribute, perform in public, or communicate to the public that audiovisual work.

The Convention also provides for “moral rights”, that is, the right to claim authorship of the work and the right to object to any mutilation, deformation, or other modification of, or other derogatory action with, the work that would be prejudicial to the author’s honor or reputation.

3. The Berne Convention allows certain limitations and exceptions on economic rights, that is, cases in which protected works may be used without the authorization of the owner of the copyright, and payment of compensation.

These limitations are commonly referred to as “free uses” of protected works and are outlined in Articles 9(2) (reproduction in certain special cases), 10 (quotations and use of works by way of illustration for teaching purposes), 10 bis (reproduction of newspaper or similar articles and use of works to report current events) and 11 bis (3) (ephemeral recordings for broadcasting purposes).

4. The Appendix to (the Paris Act of the Convention also permits developing countries to implement non-voluntary licenses for the translation and reproduction of works in certain cases, in connection with educational activities. In these cases, the described use is allowed without the authorization of the right holder, subject to the payment of remuneration to be fixed by the law.

The Berne Union has an Assembly and an Executive Committee. Every country that is a member of the Union and has adhered to at least the administrative and final provisions of the Stockholm Act is a member of the Assembly.

The members of the Executive Committee are elected from among the members of the Union, except for Switzerland, which is a member ex officio.

Question 3. Write a brief note on the universal copyright convention.

Answer:

Universal Copyright Convention: The Universal Copyright Convention (UCC), adopted in Geneva, Switzerland, in 1952, is one of the two principal international conventions protecting copyright; the other is the Berne Convention.

The UCC was developed by the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) as an alternative to the Berne Convention for those states that disagreed with aspects of the Berne Convention but still wished to participate in some form of multilateral copyright protection.

These states included developing countries as well as the United States and most of Latin America. The former thought that the strong copyright protections granted by the Berne Convention overly benefited Western, developed, copyright-exporting nations, whereas the latter two were already members of the Buenos Aires Convention, a Pan-American copyright convention that was weaker than the Berne Convention.

The Berne Convention states also became a party to the UCC, so that their copyrights would exist in non-Berne convention states. In 1973, the Soviet Union joined the UCC.

Under the Second Protocol of the Universal Copyright Convention (Paris Text), protection under U.S. copyright law is expressly required for works published by the United Nations, by UN specialized agencies, and by the Organization of American States (OAS). The same requirement applies to other contracting states as well.

Berne Convention states were concerned that the existence of the UCC would encourage parties to the Berne Convention to leave that convention and adopt the UCC instead. So the UCC included a clause stating that parties that were also Berne Convention parties need not apply the provisions of the Convention to any former Berne Convention state that renounced the Berne Convention after 1951.

Thus, any state which adopts the Berne Convention is penalized if it then decides to renounce it and use the UCC protections instead, since its copyrights might no longer exist in Berne Convention states.

Since almost all countries are either members or aspiring members of the World Trade Organization (WTO) and are thus conforming to the Agreement on Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights Agreement (TRIPS), the UCC has lost significance.

Question 4. Write a note on the patent cooperation treaty.

Answer:

Patent Co-operation Treaty: The Patent Cooperation Treaty (PCT) is an international patent law treaty, concluded in 1970.

It provides a unified procedure for filing patent applications to protect inventions in each of its contracting states.

A patent application filed under the PCT is called an international application, or PCT application. A single filing of a PCT application is made with a Receiving Office (RO) in one language.

It then results in a search performed by an International Searching Authority (ISA), accompanied by a written opinion regarding the patentability of the invention, which is the subject of the application.

It is optionally followed by a preliminary examination, performed by an International Preliminary Examining Authority (IPEA).

Finally, the relevant national or regional authorities administer matters related to the examination of application (if provided by national law) and issuance of patents.

A PCT application does not itself result in the grant of a patent, since there is no such thing as an “international patent”, and the grant of a patent is a prerogative of each national or regional authority.

In other words, a PCT application, which establishes a filing date in all contracting states, must be followed up with the step of entering into national or regional phases to proceed toward the grant of one or more patents.

The PCT procedure essentially leads to a standard national or regional patent application, which may be granted or rejected according to applicable law, in each jurisdiction in which a patent is desired.

The Patent Cooperation Treaty (PCT) assists applicants in seeking patent protection internationally for their inventions, helps patent Offices with their patent-granting decisions, and facilitates public access to a wealth of technical information relating to those inventions.

By filing one international patent application under the PCT, applicants can simultaneously seek protection for an invention in a very large number of countries.

The contracting states, the states which are parties to the PCT, constitute the International Patent Cooperation Union.

Question 5. What is the WIPO – Development Agenda?

Answer:

The World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO): The World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO) is one of the 15 specialized agencies of the United Nations (UN). WIPO was created in 1967 “to encourage creative activity, to promote the protection of intellectual property throughout the world”.

WIPO currently has 191 member states, administers 26 international treaties, and is headquartered in Geneva, Switzerland. The current Director-General of WIPO is Francis Gurry, who took office on 1 October 2008.

188 of the UN member states as well as the Cook Islands, Holy See, and Niue are members of WIPO.

Non-members are the states of Federated States of Micronesia, Nauru, Palau, Solomon Islands, and South Sudan. Palestine has permanent observer status.

In October 2004, WIPO agreed to adopt a proposal offered by Argentina and Brazil, the “Proposal for the Establishment of a Development Agenda for WIPO”—from the Geneva Declaration on the Future of the World Intellectual Property Organization. This proposal was well supported by developing countries.

The agreed “WIPO Development Agenda” (composed of over 45 recommendations) was the culmination of a long process of transformation for the organization from one that had historically been primarily aimed at protecting the interests of right holders, to one that has increasingly incorporated the interests of other stakeholders in the international intellectual property system as well as integrating into the broader corpus of international law on human rights, environment, and economic cooperation.

Several civil society bodies have been working on a draft Access to Knowledge (A2K)treaty which they would like to see introduced.

In December 2011, WIPO published its first World Intellectual Property Report on the Changing Face of Innovation, the first such report of the new Office of the Chief Economist. WIPO is also a co-publisher of the Global Innovation Index.

Question 6. Write a note on UNESCO.

Answer:

UNESCO

Copyright a traditional tool for encouraging creativity nowadays, has even greater potential to encourage creativity at the beginning of the 21st century.

Committed to promoting copyright protection since its early days (the Universal Copyright Convention was adopted under UNESCO’s aegis in 1952), UNESCO has over time grown concerned with ensuring general respect for copyright in all fields of creation and cultural industries.

It conducts, in the framework of the Global Alliance for Cultural Diversity, awareness-raising, and capacity-building projects, in addition to information, training, and research in the field of copyright law.

It is particularly involved in developing new initiatives to fight against piracy. The digital revolution has not left copyright protection unaffected.

UNESCO endeavors to contribute to the international debate on this issue, taking into account the development perspective and paying particular attention to the need to maintain a fair balance between the interests of authors and the interest of the general public in access to knowledge and information.

Question 7. Write a brief note on the TRIPS agreement.

Answer:

Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights (TRIPS) Agreement: With the establishment of the World Trade Organization (WTO), the importance and role of intellectual property protection has been crystallized in the Trade-Related Intellectual Property Systems (TRIPS) Agreement.

It was negotiated at the end of the Uruguay Round of the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT) treaty in 1994.

The general goals of the TRIPS Agreement are contained in the Preamble to the Agreement, which reproduces the basic Uruguay Round negotiating objectives established in the TRIPS area by the 1986 Punta del Este Declaration and the 1 988-89 Mid-Term Review.

These objectives include the reduction of distortions and impediments to international trade, the promotion of effective and adequate protection of intellectual property rights, and ensuring that measures and procedures to enforce intellectual property rights do not themselves become barriers to legitimate trade.

The obligations under TRIPS apply equally to all member states. However, developing countries were allowed extra time to implement the applicable changes to their national laws, in two tiers of transition according to their level of development.

The transition period for developing countries expired in 2005. For least-developed countries, the transition period has been extended to 2016 and could be extended beyond that.

The TRIPS Agreement, which came into effect on 1 January 1 995, is to date the most comprehensive multilateral agreement on intellectual property.

The areas of intellectual property that it covers are:

- Copyright and related rights (i.e. the rights of performers, producers of OT sound recordings, and broadcasting organizations)

- Trademarks including service marks

- Geographical indications including appellations of origin

- Industrial designs

- Patents including protection of new varieties of plants

- The layout designs (topographies) of integrated circuits

- The undisclosed information includes trade secrets and test data.

Issues Covered under TRIPS Agreement

The TRIPS agreement broadly focuses on the following issues:

- How basic principles of the trading system and other international intellectual property agreements should be applied.

- How to give adequate protection to intellectual property rights.

- How countries should enforce those rights adequately in their territories.

- How to settle disputes on intellectual property between members of the WTO.

- Special transitional agreements during the period when the new system is being introduced.

Features of the Agreement

The main three features of the TRIPS Agreement are as follows Standards:

The TRIPS Agreement sets out the minimum standards of protection to be provided by each Member.

Enforcement: The second main set of provisions deals with domestic procedures and remedies for the enforcement of intellectual property rights.

The Agreement lays down certain general principles applicable to all 1PR enforcement procedures.

Dispute settlement: The Agreement makes disputes between WTO Members about the respect of the TRIPS obligations subject to the WTO’s dispute settlement procedures.

In addition, the Agreement provides for certain basic principles, such as national and most-favored-nation treatment (non-discrimination), and some general rules to ensure that procedural difficulties in acquiring or maintaining IPRs do not nullify the substantive benefits that should flow from the Agreement.

The TRIPS Agreement is a minimum standards agreement, which allows Members to provide more extensive protection of intellectual property if they so wish.

Members are left free to determine the appropriate method of implementing the provisions of the Agreement within their legal system and practice.