Patent Infringement Question And Answers

Question 1. Concerning the relevant legal enactments, write short notes on the following: Potential infringement of a patent.

Answer:

Potential infringement of a patent:

- It refers to do any act that comes under the prohibited act concerning a patented invention infringement of a patent occurs without permission of the patent holder.

- It normally includes using or selling the patented invention.

- Patentee relief for infringement is under

- Interim injunction

- Damages on account of profits

- Permanent injunction

Patent Infringement Question And Answers Descriptive Questions

Question 1. Explain the powers of the Controller in respect of an application for a patent that has a substantial risk of infringement.

Answer:

The powers of the Controller in respect of an application for a patent that has a substantial risk of infringement

Section 19 of the Patents Act, 1970 covers the powers of the controller in respect of an application for a patent that has substantial risk of infringement.

- If it appears to the controller in respect of an application for a patent which has substantial risk of infringement, he may direct that a reference to that other patent, be inserted in the applicant’s complete specification by way of notice to the public.

- Such reference will not be inserted if the applicant shows to the 1 satisfaction of the controller that there are reasonable grounds for contesting the validity of the said claim of the other patent.

Question 2. Statement: Customs has lost power to interdict Patent violating goods at the Border. It can stop imports of trademark infringement but not patents By Notification Nos. 56-Customs (NT) and 57-Customs (NT) dated 22 June, 201 8 the Customs has lost its power to interdict patent infringing goods at the time of customs clearance.

In the previous dispensation, a patent registered with the customs was automatically enforced at the border by an alarm triggered by the EDI computer which raised a flag from the inward manifest when goods with registered patents entered a port.

The infringing goods import was prohibited under Sec. 11 of Customs Act, 1 962. The offense could result in the confiscation of the goods and their destruction. What is the impact of the above on technology import and domestic manufacturing? Discuss.

Answer:

Many multinationals secured Patent protection at the border without having taken the pains to go to the Court of Law to get an adjudication as regards infringement of the Patent.

This provision in the border rules was deliberately inserted in the 2007 law by certain vested interests in the customs who wanted a source of income from the legal practice of Patent law after their retirement.

They went beyond the TRI Ps Agreement at WTO which allowed waiver of Patent enforcement at the border to Developing Countries.

(The fact that Indian Border Rules on Patent enforcement go beyond WTO TRIPS was first pointed out by the Academy of Business Studies in 2007. It has taken 11 years for the Government to amend the rules and bring with it the special treatment offered to developing countries by WTO).

Many Indian manufacturers, who were earlier harassed by the Customs Authority on the ground that the goods imported infringed somebody’s registered Patent, shall get relief from the present notification.

The imposters in India who registered false Patents with the intent to blackmail the importers will also lose ground due to the present notification.

The Ramkumarcase of 2007 is of relevance here. In that case, an “inventor” from Madurai registered a false Patent for dual sim mobile phones of suitcase size. He demanded and secured, some 60 crore rupees from a reputed company (an importer in this case) like Samsung, as a license fee to import dual sim phones.

Finally, the law caught hold of him, and the IP Appellate Board overturned his Patent and thus the Customs Authority allowed free import of the dual sim phones without Ram Kumar’s NOC (No Objection Certificate).

The amendment brought into the Border Rules (the present notification in particular) is not intended to say that India shall not protect the Patent Rights of Inventors. A regular Court of Law as well as the IP Appellate Board (IPAB) is required to be moved by such Patent holder to secure an injunction to stop any infringement of his rights at the point of sale/import of an infringing article.

In the two notifications reference to the Patent Act, of 1970 has been omitted in the registration as well as enforcement system. Other PRs like copyrights, designs, and trademarks will however continue to get protection at the border.

Since the notification is made effective prospectively, all past cases shall, however, continue to be adjudicated at the customs border as per the old law.

Question 3. Ravi KamaI Bali instituted an infringement suit against Kala Tech and Ors seeking an interim injunction preventing the defendant, from making, selling, or distributing tamper-proof locks/seals as it would be the infringement of his patent.

He argued that Kala techs perform the same work, in substantially the same manner and give the same output thereby contributing to the infringement. The plaintiff asked the court to apply the Doctrine of Equivalents while considering the question of infringement of patents. Regarding this case, discuss the relevant Sections of the Indian Patent Act, of 1970.

Answer:

Ericsson is a Swedish multinational company and is the registered owner of eight patents on AMR technology, 3G technology, and Edge technology in India. It is amongst the largest patent holders in the mobile phone industry along with Qualcomm, Nokia, and Samsung.

The patents owned by Ericsson are considered to be standard essential patents. Standard essential patents are those patents that form a part of a technical standard that must exist in a product as a part of the common design of such products.

In the past two years, Ericsson has been suing various mobile handset companies on the grounds of patent infringement in India, such as Xiaomi Technology (Xiaomi), and Micromax Informatics Ltd.

(Micromax) and Intex Technologies (India) Ltd. (Intex), which are major handset and smartphone provider companies in India.

Contentions of Ericsson: Ericsson moved to the Delhi High Court against the companies named above contending that licenses on the standard essential patents were offered to be granted to these companies on fair, reasonable, and non-discriminatory (FRAND) terms.

However, these companies had refused to undertake such licenses and were using these patents without a license and accordingly were infringing Ericsson’s patents.

The decision of the High Court: The High Court held that prima facia Micromax and Xiaomi were dealing with a patent-infringing product and therefore, granted ex-parte injunction orders against them.

Furthermore, the court also directed the Customs Authorities to take note of any consignment of the products undertaken by these companies.

In the case of Xiaomi, Flipkart was also implemented in the order and was directed to get rid of all the products of Xiaomi that may be patent infringing.

Although Xiaomi managed to acquire an order allowing the company to import and sell the devices that use the chipsets imported from Qualcomm Inc., a licensee of Ericsson, it was asked to deposit an amount of 1100 for the sale of every device.

Furthermore, the court also directed Micromax to pay certain royalty rates per set to Ericsson pending the outcome of the patent infringement suit, if Micromax wanted to continue selling the devices.

The aforesaid ex-parte injunction orders by the High Court concerning selling, advertising, importing, and/or manufacturing devices that infringed the patents owned by Ericsson.

CCI Investigation Orders: Some of the aggrieved parties like Micromax decided to file a complaint under section 9(1)(a) of the Competition Act, 2002 before the Competition Commission of India (CCI) against Ericsson.

These parties claimed that Ericsson did not negotiate the terms of the license for the standard essential patents as per FRAND terms.

The main contention raised by the parties was that the royalty rates prescribed by Ericsson were excessive and discriminatory and that Ericsson, being a dominant player in the relevant market concerning essential patents, had taken advantage of its position and charged exorbitant rates for royalty from the companies for use of its patents.

The CCI considered this contention and after examining the evidence presented, agreed with the companies and passed an investigation order.

However, this order suffered a blow as the Delhi High Court passed an order restraining the CCI from passing final orders to the contention of the companies.

The Delhi High Court held that the CCI’s order resulted in raising a question of conflict of jurisdiction with the orders of the Delhi High Court.

The High Court held that the order of CCI was adjudicatory and determinative due to the nature of the order being detailed and as a result, the remedy available to Ericsson had been discarded.

Question 1. Under what provisions of the Patents Act, of 1970, can the court grant injunction orders? Is the injunction order justified in this case?

Answer:

1. Section 108 of the Patents Act, 1970 provides the power of the Court to issue injunction orders for infringement, subject to such terms, if any, as the Court thinks fit. In the case of patent infringement, an interlocutory order in the form of a temporary injunction can be granted if facts indicate:

- A prima facia of infringement;

- Balance of convenience is in favor of the plaintiff;

- Insufferable damage for the plaintiff, if injunction is not granted.

The patents owned by Ericsson are considered to be Standard Essential Patents.

Standard Essential Patents are those patents that form a part of a technical standard that must exist in a product as a part of the common design of such products.

The Indian Patents Act, of 1970 seeks to protect the rights of patent holders, and the Court, too has displayed their willingness to protect such rights.

- The Courts have often granted ex-parte injunction orders, without hearing any arguments on merits from the alleged infringers.

- But in this case, the Court failed to reckon that the patents were Standard Essential Patents. As mentioned above, Standard Essential Patents form a part of a technical standard that must exist in a product as a part of the common design of such products.

- The alleged infringers were under the obligation to ensure that the Standard Essential Patents as a technical standard existed in their products as a part of a common design.

- In the circumstances, it would have been in order if the Defendants (alleged infringers) had been given a hearing before the order had been passed.

Question 2. What are the likely implications of such ex-parte orders for the public?

Answer:

The High Court granted ex-parte injunction orders, without hearing any arguments on merits from the alleged infringers.

- Besides the fact that the Court failed to observe that the patents in these cases were Standard Essential Patents, it cannot be, he again said that it would have major implications for the development of technology and the protection of consumers.

- Consumers in these circumstances are likely not given enough choice due to such ex-parte injunction orders. In the case of Xiaomi, Flipkart was implemented in the order and the Court directed Flipkart to get rid of all the products of Xiaomi that may be patent infringing.

- Although Xiaomi managed to acquire an order allowing the company to import and sell the devices that use the chipsets imported from Qualcomm Inc., a licensee of Ericsson, it was asked to deposit an amount of INR 100 for the sale of every device.

- Thus the consumers were deprived of the products of Xiaomi before even the charges of infringement were proved.

- Furthermore, the Court also directed Micromax to pay certain royalty rates to Ericsson pending the outcome of the patent infringement suit, if Micromax wanted to continue selling the devices.

- The consumers impliedly would have to pay more for the products, as Micromax would pass on the royalty payments in the price payable by the former.

Question 3. How does the Competition Act, of 2002 deal with matters relating to IPRs?

Answer:

Section 3(5) of the Competition Act, 2002 deals with its applicability to matters relating to IPRs.

Section 3 of the Competition Act, 2002 deals with anti-competitive practices. It states that:

- No enterprise or association of enterprises or person or association of persons shall enter into any agreement in respect of production, supply, distribution, storage, acquisition, or control of goods or provision of services, which causes or is likely to cause an appreciable adverse effect on competition within India.

- Any agreement entered into in contravention of the provisions contained in sub-section Shall be void.

Section 3(5) declares that nothing contained in this Section shall restrict:

- The right of any person to restrain any infringement of, or to impose reasonable conditions, as may be necessary for protecting any of his rights which have been or may be conferred upon him under:

- The Copyright Act, 1957

- The Patents Act, 1970

- The Trade Marks Act, 1999

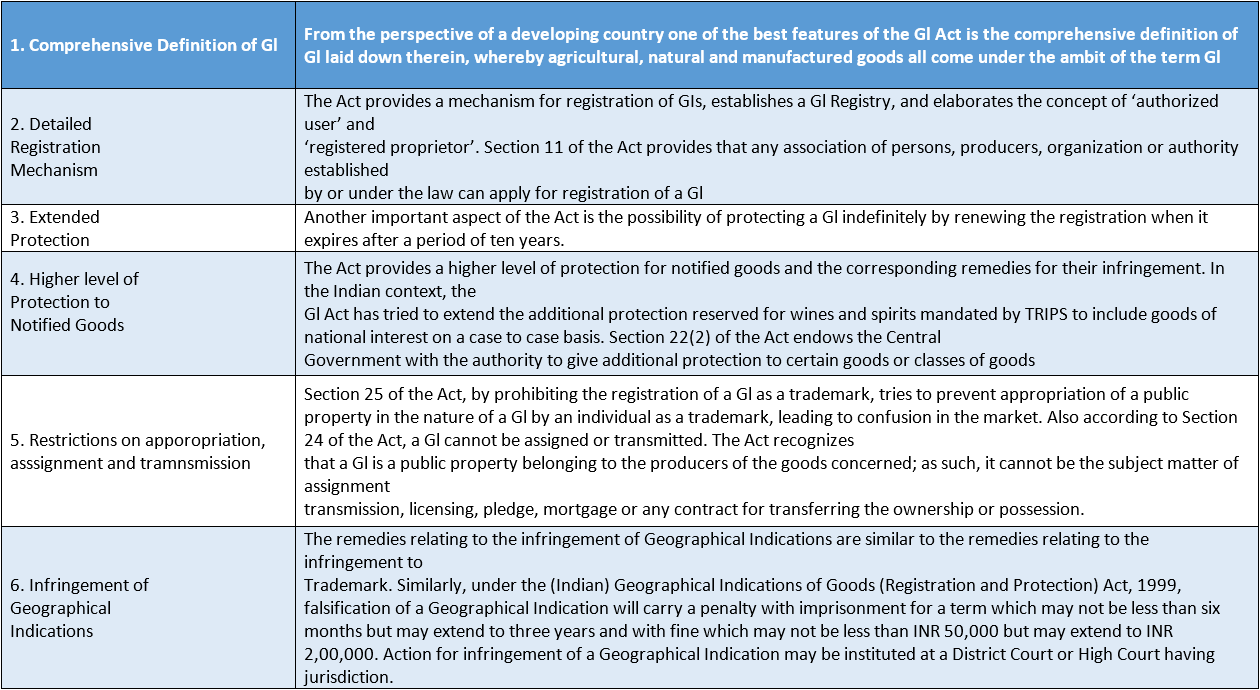

- The Geographical Indications of Goods (Registration and Protection) Act, 1999

- The Designs Act, 2000

- The Semi-Conductor Integrated Circuits Layout Design Act, 2000

Thus, the patent holder has every right to restrain the infringement of his rights.

Section 3(5) of the Competition Act, 2002 cannot come in the way of the right of the patent holder to restrain infringement of his rights unless he has imposed any unreasonable conditions while granting the license.

In cases of unreasonable conditions in the license, Section 3 of the Competition Act can be invoked. This is the legal situation on a bare reading of the Competition Act, of 2002 in conjunction with the Patent Act, of 1970.

The decision of the Delhi High Court of the CCI’s investigation orders shows that there is a possibility in patent cases that CCI’s orders may result in the overlapping with the jurisdiction of the High Courts and result in intervening with the jurisdiction of the High Court.

The role of CCI in patent cases needs to be clearer. The High Court has flagged the issue for adjudication.

Question 2. Read the following case study and answer the questions that follow: A question for adjudication, whether Section 1 07 A of the Patents Act, 1970 permits export from India of a patented invention, even if solely for uses reasonably related to the development and submission of information required under any law for the time being in force, in India, or a country other than India, that regulates the manufacture, construction, use, sale or import of any product, camp up before the High Court of Delhi.

The petitioner, Bayer Corporation (Bayer) filed a writ petition in the High Court of Delhi contending that Natco was granted a Compulsory Licence by the Controller of Patents for the drug ‘Sorafenib Tosylate’ under section 84 of the Patents Act, subject to certain terms and conditions contained therein, that one of the said terms was that the Compulsory Licence was solely to make, use, offering to sell and selling the drug covered by the patent to treat HCC and RCC in humans within the territory of India, that Natco was, however, manufacturing the product covered by the Compulsory Licence for export outside India and that the export by Natco was contrary to the terms of Compulsory Licence and amounted to infringement of the patent within the meaning of Section 48 of the Patents Act.

Natco filed a counter affidavit in the writ petition inter alia pleading

- That Natco had not exported any product (subject matter of Compulsory Licence);

- That under the scheme of the Drugs and Cosmetics Act, 1940 (Drugs Act) permission was routinely granted for export to various countries upon compliance with certain conditions and that there were similar provisions in the Western countries including Europe;

- The Patents Act also provided that the export of a patented product for generation or submission of regulatory permission was not an act of infringement;

- The export by Natco was also for regulatory purposes

- That such export was not at all barred by the compulsory license;

- That the activity of conducting studies for regulatory approval was squarely covered under section 107a of the Patents Act, and

- That natco had never exported the finished product to any party outside India for commercial purposes. Bayer, in its rejoinder to the counter affidavit aforesaid, pleaded

- That section 107a of the patents act had no application as the acts contemplated thereunder, of making, constructing, using selling, or importing a patented invention, were to be performed within the territory of India and that the information from such activity could be submitted with the regulatory authorities either in India or with the countries other than India;

- Section 107aof the act did not contemplate the export of products perse but was limited to information generated within the territory of India; and

- That export of a product covered by compulsory license under the garb of section 1 07a of the act was an abuse of the process of law.

- The senior counsel for Bayer contended that the rights, if any of natco, under section 107a of the act stood surrendered on natco obtaining the compulsory license, and thereafter natco was governed only by the terms of the compulsory license;

- That such giving up of statutory rights under section 107a of the act flowed from section 84(4) of the patents act,

- That the word ‘selling’ in section 107a of the patents act meant selling in India only and did not include export;

- Section 107a of the act, owing to its history called the ‘bolar provision’ was only to enable the activities mentioned in section 107a of the act within India and not for exports;

- That section 107a of the act was not enacted for seeking approval to manufacture a new drug in other countries;

- To read the word ‘export’ in section 107a would amount to making laws for other countries, and

Section 107a of the act used the word ‘import’ and from the absence of the word ‘export’ therein, the only logical conclusion was that exports of patented invention were outside the ambit of section 107a of the act (reproduced below).

Section 107a of the patents: “For this act, Any act of making, constructing, using, selling, or importing a patented invention solely for uses reasonably related to the development and submission of information required the time being in force, in India, or a country other than India, that regulates the manufacture, construction, use, sale or import of any product

Importation of patented products by any person from a person who is duly authorized under the law to produce and sell or distribute the product, shall not be considered as an infringement of patent rights.” It will be to reproduce Section 48 of the Copyright Act to provide the context.

Section 48: “Rights of patentees -Subject to the other provisions contained in this Act and the conditions specified in Section 47, a patent granted under this act shall confer upon the patentee-

Where the subject matter of the patent is a product, the exclusive right to prevent third parties, who do not have his consent, from the act of making, using offering for sale, selling, or importing for those purposes that product in India;

Where the subject matter of the patent is a process, the exclusive right to prevent third parties, who do not have his consent, from the act of using that process, and from the act of using, offering for sale, selling importing for those purposes the product obtained directly by that process in India.”

The said Section 48 prescribes the rights of a patentee on conferment of patent.

Those rights vest exclusively in the patentee. Axiomatically, the exercise of any of those rights by a non-patentee would be an infringement of the patent.

Counsel for Bayer contended that, the acts of a non-patentee (Natco) of making, using offering for sale, and selling patented products would be an infringement of the patent and that the patentee was entitled to approach the Courts to prevent the non-patentee from doing the said acts.

- The senior counsel for Natco argued

- That the exports intended by Natco were only for research and development purposes and for obtaining the drug regulatory approvals in the countries to which exports were intended

- Natco did not intend to export the product covered by the Compulsory Licence for commercial purposes

- Before a new drug was granted marketing approval, the drug regulatory authorities had to test its safety, efficacy, and therapeutic value by requiring clinical trials to be undertaken;

- That the Indian pharmaceutical industry was the largest exporter of generic drugs; and the biggest supplier of medicines to the developing world;

- That research and development activity with respect even to patented drugs, for submission of data to the Drug Regulatory Authority, was not infringement;

- That Section 48 of the Patents Act was subject to other provisions of the Act,

- That the rights of Natco under Section 107A were independent of the Compulsory Licence; and

- That grant of compulsory Licence could not be in negation of the rights under Section 107A.

- Further argued Natco that it was the purpose which distinguished, whether the impugned acts constituted infringement of patent or not.

If the said purpose was within the confines of Section 107A, the acts so done would not constitute infringement and the patentee would not have the right to prevent a non-patentee from doing them.

However, if the purpose of doing the acts of making, using, selling, or importing a patented invention was not solely for the purposes prescribed in Section 107A, the said acts would constitute an infringement of the patent, and the patentee would have the right to prevent a non-patentee from doing them. Hence the need for the word ‘selling’ in Section 107A.

Thus, the sale by a non-patentee of a pharmaceutical product solely for the purposes prescribed in Section 107A would also not be an infringement and cannot be prevented.

Bayer could not controvert that such selling of patented inventions, even if for profit, as long as solely for the purposes prescribed in Section 107A, is not an infringement and cannot be prevented.

The point of difference between Bayer and Natco is qua selling outside India.

Bayer contended that the word ‘selling’ in Section 107A was confined to within the territory of India and that selling of patented invention outside India even if for purposes specified in Section 107A would constitute an infringement that could be prevented by the patentee, the contention of the senior counsels for Natco was that use of the word ‘selling’ under Section A was without any such restriction of being within India only and would include selling outside India also, so long as solely for the purposes proscribed in section 107A.

An issue that was raised during the proceedings in the Court related to the Agreement on Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights (TRIPS Agreement). India as a party to the TRIPS agreement has agreed to give effect to the provisions thereof without being obliged to implement in its law more extensive protection than is required by it, provided that such protection does not contravene the provisions of the TRIPS Agreement.

Otherwise, India is free to determine the appropriate method of implementing the provisions of the TRIPS Agreement within its legal system and practice.

The objective of the TRIPS Agreement, as per Article 7 thereof, is the protection and enforcement of intellectual property rights, to contribute to the promotion of technological innovation and the transfer and dissemination of technology, to the mutual advantage of producers and users of technological knowledge and in a manner conducive to social and economic welfare and to a balance of rights and obligations.

Per Clause 1 of Article 8 of the TRIPS Agreement, member countries, in formulating and amending their laws and regulations, have the discretion to adopt measures necessary to protect public health and nutrition and to promote the public interest in sectors of vital importance to their socio-economic and technological development, provided that such measures are consistent with the provisions of the TRIPS Agreement.

Article 30 of the TRIPS Agreement entitles the member countries to provide limited exceptions to the exclusive rights conferred by a patent provided that such exceptions do not unreasonably conflict with the normal exploitation of the patent and so do not unreasonably prejudice the legitimate interest of the patent owner, taking into account the legitimate interest of third parties.

Article 31 of the TRIPS Agreement, while providing that the laws of member countries may allow the use of patented products/processes for certain purposes, vide Clause provides that such use should be predominantly for the supply of the domestic market of the member country authorizing such use.

It is the contention of counsels for Bayer, that the use permitted by Section 1 07A thus has to be for selling to the domestic market only and not for selling by way of export. The submissions of both parties traverse the contours of the Patents Act and TRIPS Agreement. Having regard to the submissions, answer the following questions.

Question 1. What is the spirit/basis for Section 107A of the Patents Act?

Answer:

Spirit/basis for Section 107A of the Patents Act:

Section 107A was incorporated/inserted into the Patents Act, 1 970 vide the Amendment Act of 2002 (Act 38 of 2002) and the same came into effect on 20th May 2003. The broad purpose and spirit behind bringing in such a provision on the statute book were to lay down certain acts that shall not be considered as amounting to an ‘infringement of a patent’. This was done in pursuance of the larger public interest.

The importance of Section 107A is to be understood in light of the provisions of Section 48 of the Act wherein the rights of the patentee (patent holder) have been laid down. A Patentee is conferred with certain exclusive rights as regards the invention (product or process) which is the subject matter of his patent.

Normally, the acts of a nonpatentee, of making, using, offering for sale, or selling patented products would be an infringement of the patent and the patentee is entitled to approach the Courts to prevent such non-patentee from doing such acts.

However, by Section 107A, the acts of a non-patentee of making, using, or selling a patented product for the purposes prescribed therein have been made as not amounting to infringement of the patent. In all such cases, the patentee cannot prevent the non-patentee from doing them.

But for Section 107A, the acts of making, constructing, using, selling, or importing a patented invention, even if for the purposes prescribed in Section 107A would have constituted an infringement of the patent.

It is thus the purpose for which the said acts are done which distinguishes, whether the acts constitute infringement of a patent or not. If the said purpose is within the confines of Section 107A, the acts so done would not constitute infringement and the patentee cannot prevent a non-patentee from doing them.

However, if the purpose of doing the acts of making, using, selling, or importing a patented invention is not solely for the purposes prescribed in Section 107A, the said acts would constitute an infringement of the patent and the patentee can prevent non-patentee from doing them.

Therefore, the consideration and the object behind the inclusion of such a provision was to allow the acts of making, using, and selling a patented invention, even during the life of the patent but solely for uses reasonably related to the development and submission of information required under the law for obtaining approval.

Question 2. Would the word ‘selling’ in Section 107A of the Patents Act include export?

Answer:

Section 107A lays down that any act of making, constructing, using, selling, or importing a patented invention solely for uses reasonably related to the development and submission of information required under any law for the time being in force, in India, or in a country other than India, that regulates the manufacture, construction, use, sale or import of any product shall not be considered as an infringement of the patent right of somebody else. The pertinent question that arises in the present set of facts, however, is, ‘whether a non-patentee thereunder can export a patented invention for such purposes’.

The answer to this question has to be sought from the language of Section 107A itself.

In the recent case, this question was answered by the Hon’ble High Court of Delhi wherein it has held that a ‘Sale by a non-patentee of a pharmaceutical product solely for the purposes prescribed in Section 107A would also not be an infringement and cannot be prevented’.

However, the further question to be answered is whether the word ‘selling’ in Section 107A is confined to within the territory of India and thus selling of patented invention outside India, even if for purposes specified in Section 107A, would constitute an infringement which can be prevented by the patentee.

To answer the question and to interpret the word ‘selling’, the Court proceeded to dissect the language of Section 107A and came to a finding that the meaning and ambit of the term ‘selling’ cannot be confined to ‘selling within India only’.

If further held that the ‘presence of the word import’ and absence of the word export’ in Section 107A does not lead to any inference of the word ‘selling’ therein being exclusive of in the course of export.

While the need for exporting was not felt due to the presence of the word ‘selling’, the need for the word ‘importing’ in Section 48 was necessary to preserve the exclusive right of the patentee and in Section 107A to allow import for purposes prescribed therein’.

Question 3. Are the provisions Section 107A and Section 48 independent of each other?

Answer:

Section 48 of the Patents Act, 1970 which is titled ‘Rights of Patentee’ starts with the wording ‘Subject to the other provisions contained in this Act and the conditions specified in Section 47, a patent granted under this Act shall confer upon the patentee….’.

Therefore, it is sufficiently clear while conferring certain rights on the Patentee to prevent others from making use of the Product or Process (as the case may be) which is the subject matter of his patent, it admits of certain exceptions carved out by Section 107A.

Section 107A provides that the acts of a non-patentee of making, using, or selling a patented product for the purposes prescribed therein shall not be considered infringement. Therefore, the patentee cannot prevent the non-patentee from doing them.

In the present set of facts, the exports intended by Natco are only for research and development purposes and for obtaining drug regulatory approvals in the countries to which exports are intended.

Natco did not intend to export the product covered by the Compulsory Licence for commercial purposes.

Therefore, as mentioned above, Section 48 of the Patents Act is subject to other provisions of the Act and the rights of Natco under Section 107A are independent of the Compulsory Licence and the grant of Compulsory Licence will not be in negation of the rights under Section 107A.

It follows that the grant of patent under the Act does not confer on the patentee’s right to prevent others from making and selling patented products if solely for purposes prescribed in Section 107A.

These are two independent provisions, admitting of no overlap or need to read one as a proviso (and consequently narrowly) to another.

The rights conferred on non-patentees under Section 107A are to be interpreted following the same rules as the rights of a patentee and are not to be read narrowly or strictly to reduce the ambit of Section 107A, as is the rule of interpretation of statutes about provisos or exceptions. Section 107A does not carve out an exception to the exclusive right conferred by the grant of a patent.

Question 4. Discuss the relevance of Article 31(f) of the TRIPS Agreement in the export.

Answer:

The relevance of Article 31(f) of the TRIPS Agreement in the export

Section 107A of the Patents Act, 1970 is not an exception that is carved out to the exclusive rights conferred by the grant of a patent. The exclusive right conferred by the grant of a patent concerning selling, offering for sale, and thereby profiteering and earning from the patent is confined only during the term of the patent.

Section 107A permits the sale of a patented product during the term of the patent but only to obtain regulatory approvals for manufacturing and marketing the patented product after the expiry of the term of the patent.

The purchasers of a patented product for such a purpose would be few and negligible in comparison to the consumers of the patented product. There is nothing in the provisions of the TRIPS Agreement to suggest that reading the word ‘selling’ in Section 107A as including ‘by way of export’, would violate the TRIPS Agreement.

TRIPS Agreement specifically vests discretion in the member countries to adopt measures in their laws that are necessary to promote public interest in sectors of vital importance to their socio-economic development.

Even if it were to be considered that clause of Article 31 thereof allows domestic operation only of Bolar provision, the Indian Parliament while enacting the Patents Act, 1970 was entitled to, having regard to the extent of the Indian Generic Industry, permit export for purposes of Section 107A.

Patents Act is concerned with the protection of the rights of the patentees in India only and not outside India. Neither the legislature nor the Courts in India can impose any conditions on the use of the goods exported once they reach the destination country or ensure that such goods continue to comply with the laws in India.

The use of the goods in a foreign country would be subject to the laws of that country and cannot be regulated by the laws of India or orders of the Courts in India. Even if it were to be believed that the patented invention once exported from India for the purposes prescribed in Section 1 07A may be used for other purposes, it is for the patentee to enforce its rights if any in that country.

The laws of India are only concerned with the sale by way of export from this country being for the purposes prescribed. As long as the sale by way of export is declared to be for purposes of Section 1 07A and there is nothing to suggest that it is otherwise, no fetters can be imposed.

Patent Infringement Question And Answers Topic Not Yet Asked But Equally Important For Examinations Short Notes

Question 1. Write a brief note on the Doctrine of Equivalents and Doctrine of Colorable Variation.

Answer:

Doctrine of Equivalents and Doctrine of Colorable Variation:

Patent infringement generally falls into two categories: literal infringement and infringement under the doctrine of equivalents.

The term “literal infringement” means that every element recited in a claim has identical correspondence in the allegedly infringing device or process.

However, even if there is no literal infringement, a claim may be infringed under the doctrine of equivalents if some other element of the accused device or process performs substantially the same function, in substantially the same way, to achieve substantially the same result.

The doctrine of equivalents is a legal rule in most of the world’s patent systems that allows a Court to hold a party liable for patent infringement even though the infringing device or process does not fall within the literal scope of a patent claim but is equivalent to the claimed invention.

An infringement analysis determines whether a claim in a patent literally “reads on” an accused infringer’s device or process, or covers the allegedly infringing device under the doctrine of equivalents. The steps in the analysis are:

- Construe the scope of the “literal” language of the claims.

- Compare the claims, as properly construed, with the accused device or process, to determine whether there is literal infringement.

- If there is no literal infringement, construe the scope of the claims under the doctrine of equivalents.

The doctrine of equivalents is an equitable doctrine that effectively expands the scope of beyond their literal language to the true scope of the inventor’s contribution to the art. However, there are limits on the scope of equivalents to which the patent owner is entitled.

The doctrine of Colorable Variation: A colorable variation or immaterial variation amounting to infringement is where an infringer makes a slight modification in the process or product but takes in substance the essential features of the patentee’s invention.

In Lektophone Corporation v. The Rola Company, 282 U.S. 168 (1930), a patent holder’s patents were for sound-reproducing instruments for phonographs.

According to the patent application, the size and dimensions of the invention were the essence of the patent. The patent holder claimed that a radio loudspeaker manufactured by the defendant (manufacturer) infringed the patent.

The manufacturer’s devise also had a central paper cone, but the cone was smaller than that of the patented device and that constituted colorable alteration.

The court held that because of colorable alterations of the manufacturer’s devise, it would not accomplish the object specified in the patent claims and hence did not infringe upon the patent holder’s claims.

There are five ways to justify a case of patent infringement:

- Doctrine of Equivalents

- Doctrine of Complete Coverage

- Doctrine of Compromise

- Doctrine of Estoppel

Doctrine of Superfluity Sometimes the end user is not even aware that he or she is using a patented item unlawfully.

Other times, there are too many people using the item to sue all of them. Rather than suing end users, it might be best to sue those who are knowingly trying to infringe on a patent.

Question 2. Write a Brief Note on the Power of Controller in Case of Potential Infringement.

Answer:

Power of Controller in case of Potential Infringement: Section 19 of the Patent Act, of 1970 provides that-

1. If, in consequence of the investigations required under this Act, it appears to the Controller that an invention in respect of which an application for a patent has been made cannot be performed without substantial risk of infringement of a claim of any other patent, he may direct that a reference to that other patent shall be inserted in the applicant’s complete specification by way of notice to the public, unless within such time as may be prescribed—

- The applicant shows to the satisfaction of the Controller that there are reasonable grounds for contesting the validity of the said claim of the other patent; or

- The complete specification is amended to the satisfaction of the Controller.

2. Where, after a reference to another patent has been inserted in a complete specification in pursuance of a direction under sub-section (1)-

- That other patent is revoked or otherwise ceases to be in force; or

- The specification of that other patent is amended by the deletion of the relevant claim; or

- It is found, in proceedings before the court or the Controller, that the relevant claim of that other patent is invalid or is not infringed by any working of the applicant’s invention, the Controller may, on the application of the applicant, delete the reference to that other patent.

Review of Controllers’ Decision (Procedure)

- The statute provides for review of the Controller’s decision under section 77 of the Patents Act 1970. The applicant need to file Form 24 within the time limits prescribed in Rule 130.

- The Controller shall act per the prescribed norms under Rule 130 and decide that matter on the merit of each case.

- The Controller, in any proceeding before him under the Patents Act, 1970, shall have the powers of a civil court while trying a civil suit under the Code of Civil Procedure, 1908 (5 of 1908). The review under section 77 is dealt with in the like manner.

Who may file the review Petition:

Any person considering himself aggrieved—

- By a decree or order from which an appeal is allowed, but from which no appeal has been preferred,

- By a decree or order from which no appeal is allowed, Grounds for review:

Grounds for review:

- Discovery of new and important matter or evidence which, after the exercise of due diligence was not within the petitioner’s knowledge or could not be produced by him at the time when the decree was passed or order made, or

- On account of some mistake or error apparent on the face of the record or, for any other sufficient reason.

A party who is not appealing from a decree or order may apply for a review of judgment notwithstanding the pendency of an appeal by some other party except where the ground of such appeal is common to the applicant and the appellant, or when, being respondent, he can present to the Appellate Court, the case on which he applies for the review.

Hon’ble Supreme Court of India on reviews:

Hon’ble Supreme Court in Satyanarayan Laxminarayan Hegde and Ors. vs. Mallikarjun Bhavanappa Tirumale (AIR 1960 SC 137) held that “An error which has to be established by a long drawn process of reasoning on points where there may conceivably be two opinions can hardly be said to be an error apparent on the face of the record.

Where an alleged error is far from self-evident and if it can be established, it has to be established, by lengthy and complicated arguments, such an error cannot be cured by a Writ of Certiorari according to the rule governing the power of the Superior Court to issue such a writ.”

The very fact that the Learned Counsel for the appellant had to labor for several hours to make her submissions would show that if there were errors in the decisions, it had to be decided only by a process of reasoning that is not apparent on the face of the records.

Question 3. Write a Brief Note on the powers of the Intellectual Property Appellate Board.

Answer:

Powers of the Intellectual Property Appellate Board

According to the amendments introduced to the Patents Act, 1970 in 2002, a specialized forum called the Intellectual Property Appellate Board (“!PAB”) was constituted by the Central Government on September 15, 2003, to hear and adjudicate appeals against the decisions of the Registrar under the Trade Marks Act, 1999 and the Geographical Indications of Goods (Registration and Protection) Act, 1999.

In India, only High Courts have the power to deal with both infringement and invalidity of patents simultaneously.

Now the IPAB has since April 2, 2007, been extended to Patent law and is now authorized to hear and adjudicate upon appeals from most of the decisions, orders, or directions made by the Controller of Patents.

Also, vide a notification; all pending appeals from the Indian High Courts under the Patents Act were transferred to the IPAB from April 2, 2007.

The IPAB has its headquarters in Chennai and has sittings in Chennai, Mumbai, Delhi, Kolkata, and Ahmedabad.

Jurisdiction: Every appeal from the decision of the Controller to the IPAB must be made within three months from the date of the decision, order, or direction, as the case may be, or within such further time as the IPAB may permit, along with the prescribed fees.

Exceptions: The IPAB (Procedure) Rules, 2003 exempt orders passed by the Central Government of India for inventions on defense purposes, including directions of secrecy in respect of such inventions, revocation if the patent is contrary or prejudicial to the public interest, or pertains to atomic energy, from the purview of appeal to the IPAB.

Transfer of pending proceedings to IPAB: The IPAB is the sole authority to exercise the powers and adjudicate proceedings arising from an appeal against an order or decision of the Controller.

All the cases on revocation of patent, other than a counter-claim in a suit for infringement, and rectification of register pending before the Indian High Courts shall be transferred to the IPAB.

In case of a counter-claim in a suit for infringement, the Indian High Courts continue to be the competent authority to adjudicate on the matter.

The IPAB also has exclusive jurisdiction on matters related to the revocation of patents and rectification of the register. The IPAB in its sole discretion may either proceed with the appeals afresh or from the stage where the proceedings were transferred to it.

Question 4. Write short notes on the following:

- Direct Infringement

- Declaration as to non-infringement

- Defenses for infringement

Answer:

Direct Infringement: Direct patent infringement is the most obvious and the most common form of patent infringement.

Direct patent infringement occurs when a product that is substantially close to a patented product or invention is marketed, sold, or used commercially without permission from the owner of the patented product or invention.

Declaration as to non-infringement: Under Section 1 05 of the Act, any person after the grant of publication of the patent may institute a suit for a declaration as to non-infringement.

For this, the plaintiff must show that:

- He applied in writing to the patentee or his exclusive licensee for a written acknowledgment to the effect that the process used or the article produced by him does not infringe the patent and

- The patentee or the licensee refused or neglected to give such an acknowledgment. It is not necessary that the plaintiff must anticipate an infringement suit.

Defenses for infringement:

1. In any suit for infringement of a patent, every ground on which it may be revoked under Section 64 shall be available as a ground for defense.

In any suit for infringement of a patent by the making, using, or importation of any machine, apparatus, or other article or by the using of any process or by the importation, use, or distribution of any medicine or drug, it shall be a ground for defense that such making, using, importation or distribution is under any one or more of the conditions specified in Section 47 [Section 107] In Cadila Pharmaceuticals Ltd. v.

Instacare Laboratories Pvt. Ltd., 2001(21) PTC 472 (Guj), the Gujarat High Court observed that Section 107 expressly empowered a defendant to defend any suit for infringement of a patent. Every ground on which a patent could be revoked under section 64 was available as a ground of defense.

Though the defendant had chosen not to give notice of opposition under section 25 of the Act or to apply for revocation under section 64 of the Act, he still had the right to defend his action on any ground on which the patent could be revoked under section 64 of the Act.

Patent Infringement Question And Answers Descriptive Questions

Question 1. Enumerate the acts that do not amount to infringement.

Answer:

The law however enumerates certain exceptions to infringement:

Experimental and Research:

Any patented article or process can be used for the following purposes:

- Experiment

- Research

- Instructing pupils

It is also permitted to make, construct, use, sell, or import a patented invention solely for the uses reasonably related to the development and submission of information required under any law for the time being in force, in India, or in a country other than India, that regulates the manufacture, construction, use, sale or import of any product.

All such acts, if within the bounds as created above, cannot be challenged as infringing the rights of the patentee.

Parallel Importation under certain conditions: A patented article or article made by using the patented process can be imported by the government for its use. Also, a patented process can be used by the government solely for its use. Moreover, the government can import any patented medicine or drug for its use or distribution in any dispensary, hospital, or other medical institution maintained by the government or any other dispensary, hospital, or medical institution notified by the government. [Section 27 & 47]

Jurisdiction: The legal provisions concerning jurisdiction are provided in Section 104 of the Patents Act, 1970. Before dealing with jurisdiction, it may be pointed out that the courts in India receive

Patent Administrative Cases and Patent Infringement Cases. In patent administrative cases, the Indian Patent Office is the defendant. These types of cases include disputes on the grant of a patent, patent invalidation and upholding, and compulsory licensing.

In patent infringement cases, the patentee or patent assignees pursue damages against willful infringement conduct by the alleged infringer.

These cases include infringement of patents, disputes relating to ownership of patents, disputes regarding patent rights or right for application, patent contractual disputes, contractual disputes of assignment of patent rights, patent licensing, and disputes relating to the revocation of patents.

Period of Limitation: The period of limitation for instituting a suit for patent infringement is years from the date of infringement.

Burden of Proof: The traditional rule of burden of proof is adhered to concerning patented products and accordingly in case of alleged infringement of a patented product the ‘onus of proof’ rests on the plaintiff.

However, the TRIPS-prompted amendment inserted by way of Section 104 (A) has ‘reversed the burden of proof’ in case of infringement of the patented process.

Under the current law, the court can at its discretion shift the burden of proof on the defendant, in respect of process patent if either of the following two conditions is met:

The subject matter of the patent is a process for obtaining a new product; there is a substantial likelihood that an identical product is made by the process and the plaintiff has made reasonable efforts to determine the process used but has failed.

[Section 1 04 (A)] While considering whether a party has discharged the burden imposed upon him under Section 104(A), the court shall not require him to disclose any manufacturing or commercial secrets, if it appears to the court that it would be unreasonable to do so.

Question 2. What are the different types of Patent Infringement?

Answer:

Types of Patent Infringement:

There are different ways a patent could be infringed. Some of the types of patent infringements include:

Direct Infringement: This occurs when a product covered by a patent is manufactured without permission. Direct patent infringement is the most obvious and the most common form of patent infringement.

Direct patent infringement occurs when a product that is substantially close to a patented product or invention is marketed, sold, or used commercially without permission from the owner of the patented product or invention.

Indirect Infringement and Contributory infringement: An indirect infringer may induce infringement by encouraging or aiding another in infringing a patent. Indirect patent infringement suggests that there was some amount of deceit or accidental patent infringement in the incident.

For instance, A holds a patent for a device and B manufactures a device that is substantially similar to A’s device. B is supplied with a product from another person C to facilitate the manufacturing of B’s device.

If the device so manufactured by B infringes upon A’s patent, then person C indirectly infringes A’s patent. Further, if such a product is knowingly sold or supplied, it may lead to “contributory infringement”. In the above example, if the person C knowingly supplies the product to B then the infringement is construed as contributory infringement.

Contributory Infringement: This occurs when a party supplies a direct infringer with a part that has no substantial non-infringing use.

Literal Infringement: This exists if there is a direct correspondence between the words in the patent claims and the infringing device.

Even if an invention does not infringe the patent, it may still infringe under the doctrine of equivalents. A device that performs the substantially same task in substantially the same way to achieve substantially the same result infringes the patent under this doctrine. If the court finds infringement, it must still determine whether the infringement was willful.

Willful Infringement: Willful infringement involves intentional disregard for another’s patent rights and encompasses both direct and intentional copying and continued infringement after notice. Patent users and inventors should employ patent attorneys to ensure that the use of a patent is valid and non-infringing. Even if the infringement is later found, the attempt to secure a legal opinion is evidence that the infringement was not willful.